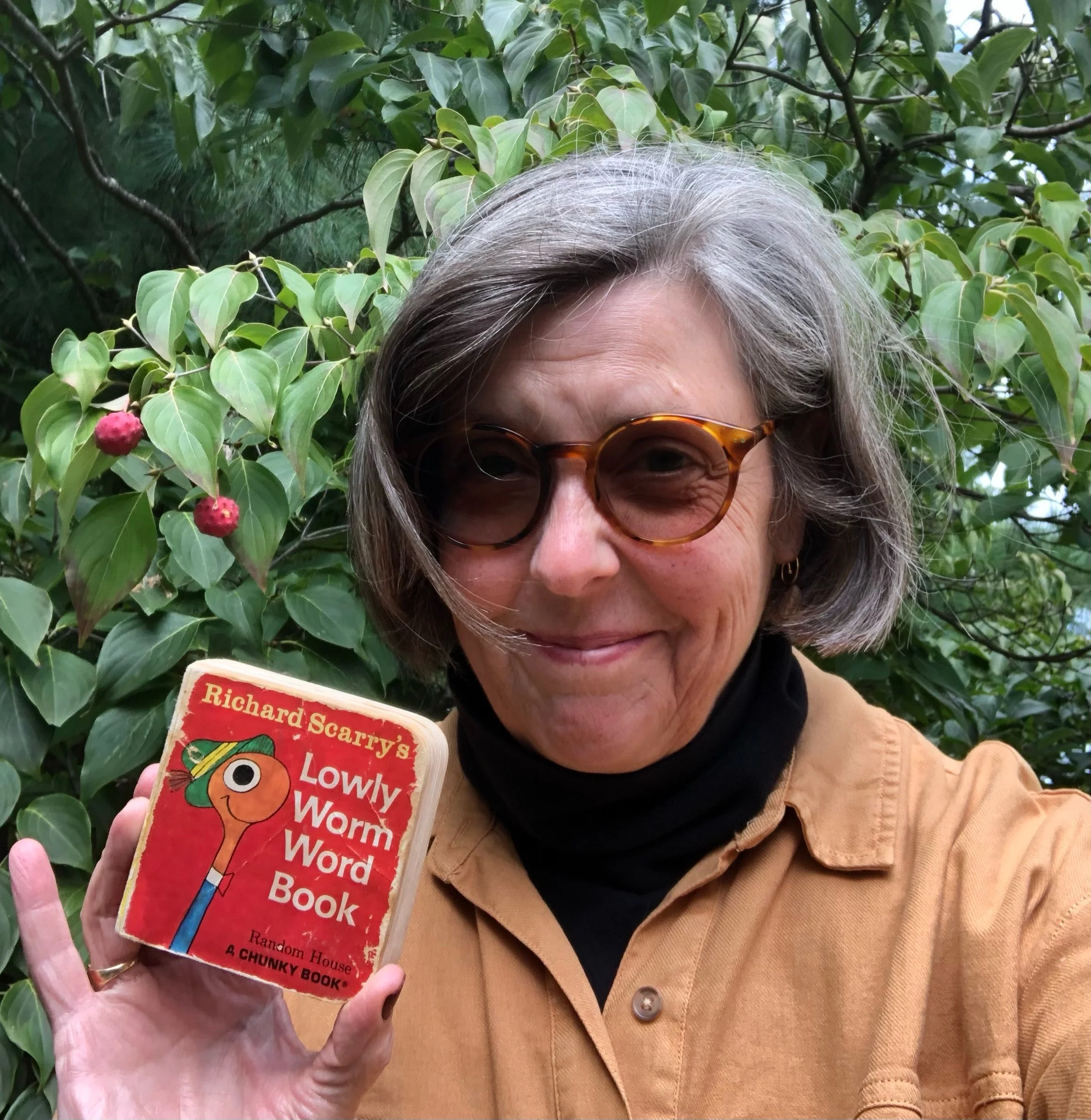

Consider the Humble Board Book By Susan Claus

We are so excited to have Susan Claus join us today to share information about Children’s Board Books!

Susan Claus is a children’s librarian, writer, and illustrator from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is happiest outside on slightly rainy days. Susan makes sure to let her inner child out every day to play.

Before the 1940’s, “books for children” meant “books for children who had learned to read”. Publishers pushed out a few books for parents to buy around the holidays, but most of the publishing was aimed at the public library market, and for schools. Librarians, back in the day, were staunch prescriptionists (“We’ll TELL you what’s good for you”), defenders of children’s fragile souls, making sure that nothing harsh, ugly, or silly contaminated the blank pages of their unformed minds. Publishers didn’t see the children’s book market as lucrative.

The post-war baby-boom suddenly delivered to the publishing industry a huge wave of children and parents eager to buy interesting books. Educators at New York’s Bank Street School did an end-run around the gate keeping librarians and produced books about the everyday experience of children, the harsh, the ugly, and the silly included. Books that were fun and engaging. And marketable! Publishers took note, and enlisted an army of writers and illustrators to produce wonderful picture books. But still, these books were targeted at children who could read.

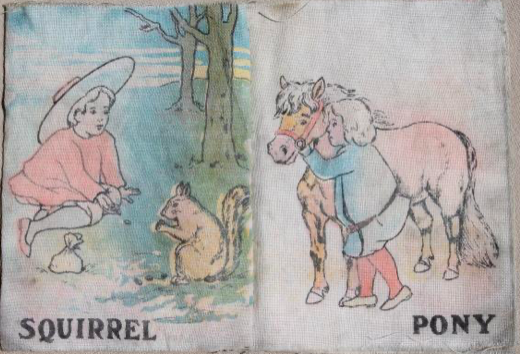

Pre-1940, a baby might be given a cloth book; two cotton rectangles, sewn down the middle, to play with. Cloth books were toys, not brain fodder. Babies and toddlers were viewed as human dumplings, tiny barbarians bent on the destruction of any books that came into their pudgy hands, and, until they could talk, not given credit for having much going on “upstairs”.

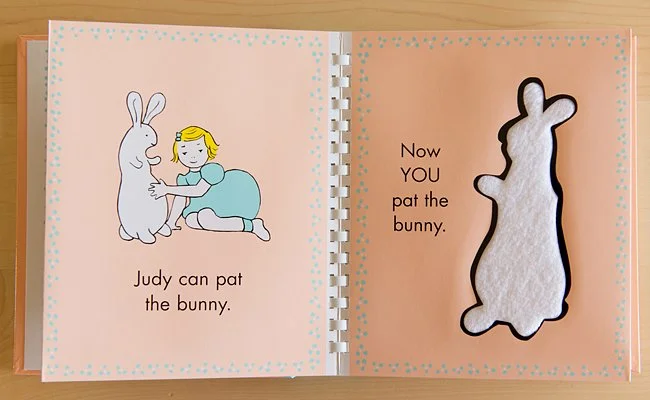

The arrival of Pat the Bunny by Dorothy Kunhardt in 1940 changed the thinking about baby books. Pat the Bunny had sturdy, doubled pages that were hard to tear. Each spread had simple words, a simple drawing, and a texture, piece of cloth, or hole in the page that related to the image. Parents and the babies on their laps encountered the pages together, and parents could see their babies engaging those pages in ways that proved the “wheels” were turning. Parents began to demand books that fed babies’ minds, and publishers were quick to deliver.

Books with cardboard pages, that were hard to tear, and fine to chew on, gave babies and toddlers books of their own. Most were simple concept books; word books, opposites, counting books and ABCDeries. A few had simple, linear stories.

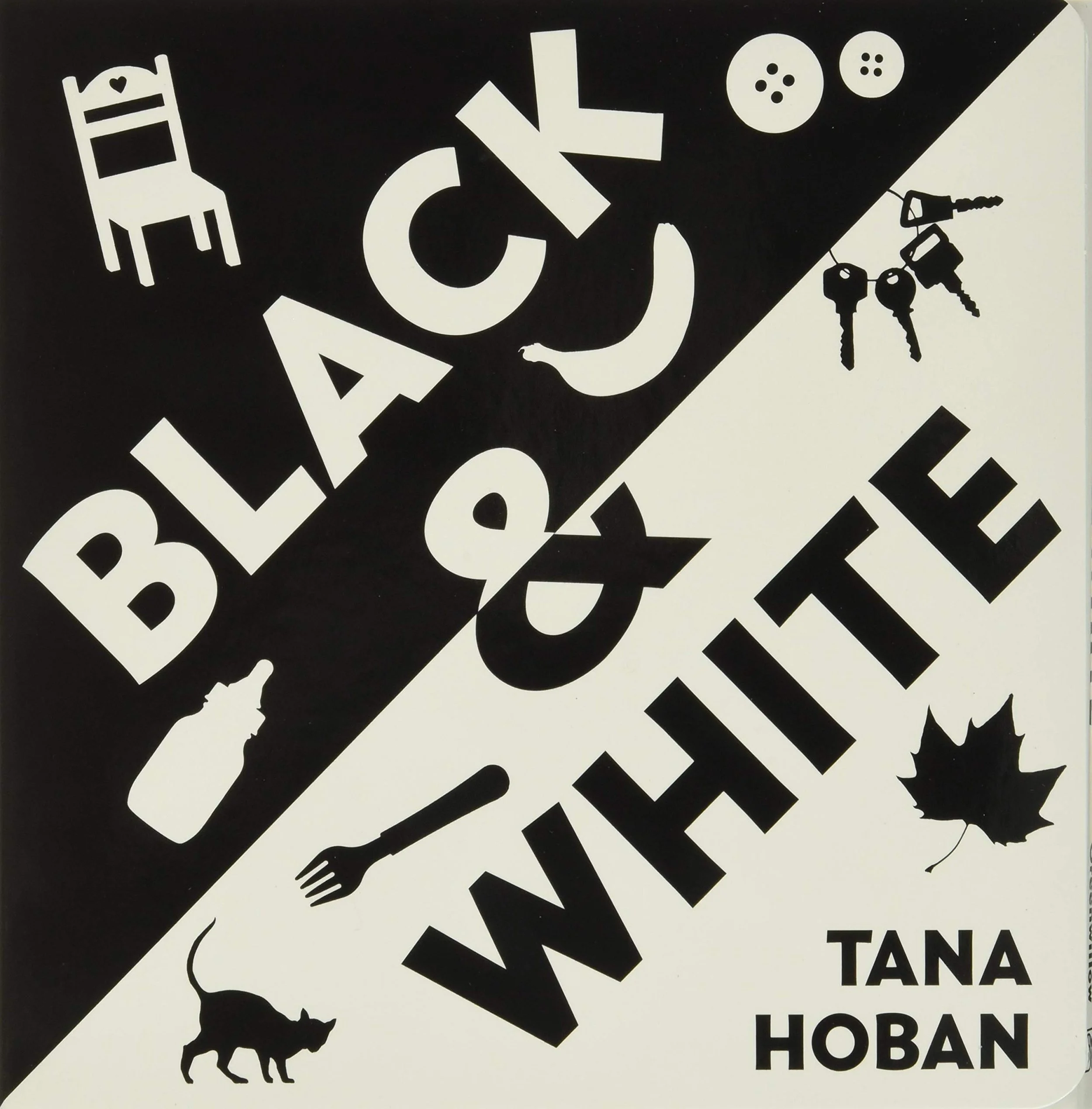

Researchers in the 1980s began to study brain development in children in new ways, courtesy of technology like magnetic imaging, and proved that babies’ brains were not just little unformed blobs, but full of billions of busy neurons firing and making connections. Other researchers studied how babies process vision, and discovered that the gentle pastel colors that traditionally surrounded them were actually hard for babies to see.

Publishers responded with board books designed to stimulate babies’ brains with bold black and white images, and colorful pages with sharp contrast.

The early brain development research also showed how very interested babies were in looking at faces, so board books with photographs of babies soon crowded bookstore shelves.

Most board books were created by publishers in-house, with writers and illustrators uncredited. But the explosion of board book publishing caught the attention of author illustrators like Rosemary Wells and Sandra Boynton, who pushed the small publishing niche into a full-fledged genre.

As the demand for board books expanded, publishers looked to their back lists and began to repackage picture book classics in board book format.

Board books as a genre continues to expand. In the past few years, writers and illustrators have developed cheeky high-concept one-word-per-page board book “retellings” of literary classics like Moby Dick and Jane Eyre.

Biographies were once a school-library exclusive, but board book biographies of Freida Kahlo and Coco Chanel can now be found in many strollers, along with “baby’s first book of physics”.

Babies & toddlers now have hundreds of sturdy, high-quality board books to handle and enjoy. But beyond enjoyment, having books they can handle sets them up to be successful future readers. They develop print awareness, print motivation, small motor skills, hand-eye coordination, and a visual vocabulary.

Hooray for the humble board book!

PS: Want to take a gander at some fresh new board books? Try this list from Book Riot.