Finding Picture Book Power in the ‘Lost’ Art of Letter Writing with Rebecca Randall

We are so excited to have Rebecca Randall join us today to share information about Epistolary Picture Books!

Rebecca is a writer, editor and brand builder based in New York. She has crafted the narratives of many well-known characters, from cartoon bunnies to real-life CEOs. Lately she’s been helping college applicants tell their own stories. Rebecca is a graduate of Dartmouth College and the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Rebecca can be reached at https://www.linkedin.com/in/brandkitchen/.

“A graduate thesis on Epistolary Picture Books – is that even a thing?” I’ve been asked this more than once. After all, the youngest readers haven’t mastered their ABCs, never mind seen that ancient artifact known as a postage stamp.

After analyzing over 50 of them, I’m happy to report the “EPB” is a thing: a multi-faceted narrative form that lets writers craft a stunning range of memorable characters.

“Epistolary” refers to stories told through written material – diaries, schoolwork, and most often, letter correspondence. Exchanges lean on first-person narration, offering writers the benefits of intimacy, voice -- and unreliability – in characters readers feel they get to know. And every missive has an addressee, creating a built-in mechanism to reveal traits and motivations. Mentor texts illuminate the form’s distinctive features.

How a character writes gives unique clues

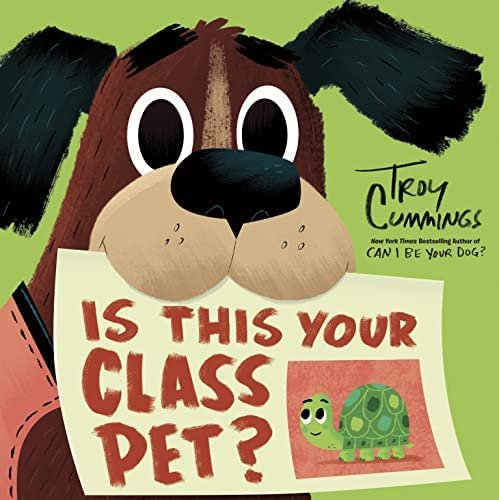

In Troy Cummings’ latest EPB, IS THIS YOUR CLASS PET?, eager Arfy is a library helper dog on a rescue mission. Arfy’s first letter recaps his assets: “Soft fur, good for cuddles… And I hardly ever drool! (except at lunchtime.)” When a turtle hitches a ride home with him, Arfy writes to school staff to reunite the pet with its class.

Arfy’s letters ooze with personality via doodles, pawprint signatures or an exuberant “WOOF!!” Clever names, media and writer-voices unveil correspondents, like Coach Burpee who diagrams X’s and O’s from his clipboard, telling Arfy to “Chin up!”

Exchanges are digital, too, featuring DMail – Mail for dogs, an auto-reply from Principal Peppercorn, and a class video-chat finale. Who can’t relate to Arfy in headphones, facing a Zoom-like grid of faces and chat bubbles?

What a character writes – or doesn’t – speaks volumes

First-person POV limits what can be told. But the visual narrative of a PB can offset this. DEAR MRS. LARUE: LETTERS FROM OBEDIENCE SCHOOL, by author-illustrator Mark Teague, delivers a disingenuous dogtagonist.

Ike, a feisty terrier, pleads with his owner to be released from “prison.” Except… illustrations show the “horror” of his confinement: palm trees and poolside pampering. Ike is the ultimate unreliable narrator. Dark visuals frame his melodramatic missives in a “split screen” alongside sunny reality, letting readers in on the joke. Teague also integrates third-person epistolary elements like newspaper articles. The result: kids experience divergent perspectives of the same event.

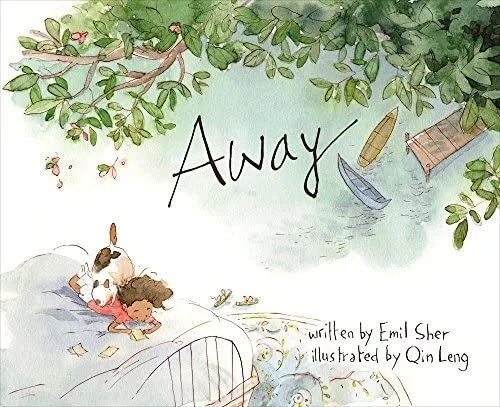

Letters aren’t the only way to correspond. In AWAY by Emil Sher and Qin Leng, a girl struggles with going to sleep away camp. The story unfolds through an exchange of stickies with her mom, in a feat of creative concision at 250 words.

Amid everyday scribbles about milk and math homework, Skip and her mom negotiate. “I’m not going. Not EVER!” Skip declares. Mom pushes back: “You won’t be gone forever. It’s only 2 weeks.” But mom is something of an unreliable narrator. A calendar and a photo album enhance the stickie dialog for a tender, pivotal reveal: Mom was once an anxious camper too.

To whom a character writes shapes the story

Stickies give Skip an outlet to work through her emotions. Poems play a similar role in the lyrical EPB, DEAR SUBSTITUTE by Liz Garton Scanlon /Audrey Vernick and Chris Raschka.

When a substitute teacher appears, an unnamed narrator turns to verse to express the many ways this upends her day. Fifteen poems reveal the heartbeat of a girl confronting change, (“Dear Homework That I Stayed Up Late Doing, …”). Addressees don’t write back; they don’t need to. Framing each poem to a specific person or thing uses the emotional currency of classroom routines to reflect the character’s yearnings and arc of discovery.

Epistolary form’s focus on relationships makes it a natural for friendship stories. When a solitude-seeking owl in Julie Falatko and Gabriel Alborozo’s YOURS IN BOOKS is upset by noisy neighbors, he writes a bookshop for help. “Dear Sirs,” the formal Owl T. Fencepost writes, to order How to Soundproof Your Forest Dwelling. “Sirs” is clever owner B Squirrel, who can’t fill the order but senses Owl’s needs, and delivers her own ideas. Vivid vocabulary differentiates the book lovers, who signal their growing friendship through increasingly familiar shorthand, while surprise enclosures hint to the ultimate literary escape: an in-person meet-up.

These are a just few EPBs that ring with character and sing through correspondence – ideal read-alouds. But once you start looking, you’ll find epistolary mentor texts across every PB type: historical fiction, biography, fractured fairy tale – even wordless.

P.S. An EPB promise: the more you read, the more you’ll be inspired to write your own.