Narrative Nonfiction with Julie Leung

We are so excited to have Julie Leung join us today to share information about narrative nonfiction picture books!

By day, Julie Leung is a marketing director at Random House, specializing in sci-fi/fantasy. By night, she is a children’s book author. Her debut series, Mice of the Round Table was praised as a “winning new adventure,” by Kirkus Reviews. She is also the author of Paper Son: The Story of Tyrus Wong, The Fearless Flights of Hazel Ying Lee, and more.

I first read about Tyrus Wong through his New York Times obituary. It was December 2016, and I was reckoning with the anti-immigrant policies that came with the new presidential administration. I was also looking for my next writing project after completing my middle grade series, Mice of the Round Table.

It was the perfect time to encounter this incredible life story of a man who lived to be 106 years old -- a visual artist who made groundbreaking contributions to American animation and art, particularly through his work on the Disney classic, Bambi. He was also a man who, according to the laws of the time, immigrated to the United States illegally as a paper son.

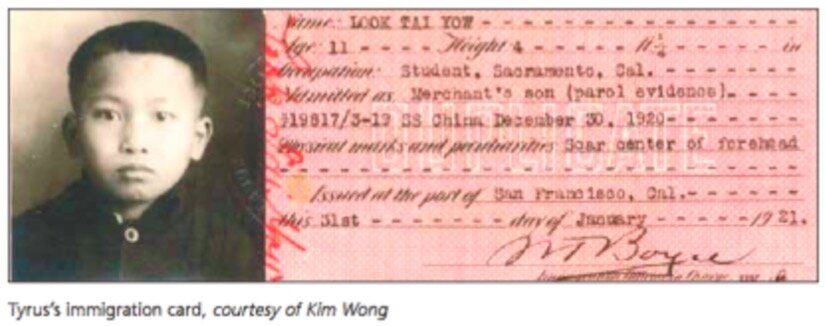

During the many decades that the Chinese Exclusion Act was in place, a few exceptions were made: if one were a person of high status (such as a merchant or scholar) or related to a Chinese person already living in the country. These exceptions kicked off a black market of false identification papers sold in China, where desperate immigrants would often claim blood relations to Chinese who were already in America, i.e. becoming a son or daughter to someone ‘on paper’ only.

Tyrus and his father, bearing papers claiming to be of merchant class, arrived in San Francisco in 1919. When they were stopped at Angel Island Immigration Station, 10-year-old Tyrus was separated from his father and detained for over a month. When you watch video interviews where Tyrus recounts that experience, you can see how that trauma still haunts him.

I wanted more people to know about Tyrus Wong’s legacy and this little-taught history around the Chinese Exclusion Act and the ‘paper son’ phenomenon. I wanted to convey how immigrants, wanted or not, make huge contributions to this country. How could I encapsulate all this in a nonfiction picture book?

Step 1: I drafted an initial outline of the manuscript based on the obituary alone, establishing the key beats in Tyrus’s life I thought would be important.

Step 2: I began my research in earnest. I read as many articles as I could find and watched numerous interviews with Tyrus on YouTube. My agent helped me source this fantastic documentary called Tyrus directed by Pamela Tom. I also found a retrospective art book published by the Walt Disney Foundation. Both proved to be instrumental.

Step 3: After I fleshed out the manuscript with these researched details, I began to look for places to infuse poetic impact. From the beginning, I always knew I wanted to end the book with old man Tyrus flying his kite, facing the same ocean he crossed as a child. But other moments came to the forefront at this research stage -- when I read about how Tyrus would work as a janitor at his art school, I added a moment where he imagines that his mop is a paint brush.

The motif of paper surfaced insistently: paper as Tyrus’ medium for his art, the newspapers his father used to teach him calligraphy, the fact that he was a paper son. I thought about my own parents who immigrated from a similar village just 40 miles away from where Tyrus’s family lived.

Becoming an immigrant is rewriting one’s own fate—throwing out what has been written for you and determining your own story on a new page of paper.

And thus, my refrain of “life in America could be like a blank paper” where Tyrus could leave his “mark” came to be.

Step 4: At this point, my agent and I felt that the manuscript was in good shape to go on submission. It eventually landed at Random House Children’s, in the capable hands of Anne Schwartz, where she helped me streamline and clarify certain concepts so that children could grasp them more easily. I also reached out to the Wong family at this time who provided additional insights and most importantly to me, their blessing on the project.

Step 5: A final round of fact-checks and copy edits later, and my words went to the brilliant illustrator Chris Sasaki. How did he manage to take that 1,500 word manuscript and transform it into pure visual poetry? You’ll have to ask him!