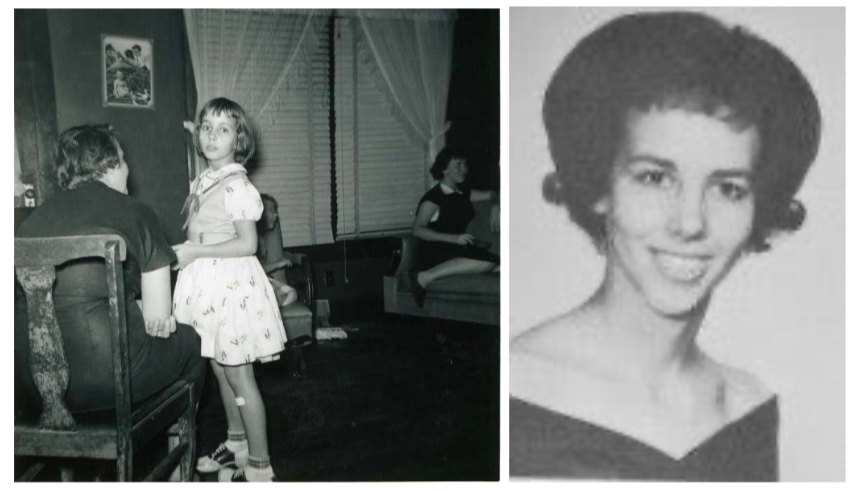

We are so excited to have Susan Claus join us today to share information about Expository Nonfiction Picture Books!

Susan Claus is a children’s librarian, writer, and illustrator from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is happiest outside on slightly rainy days. Susan makes sure to let her inner child out every day to play.

Exposition:

An explanation of something

A piece of writing that explains

The first part of a piece of music in which the theme is presented

A public exhibition

Webster’s Kids’ Definitions merriumwebster.com accessed via Ecosia, January 11, 2023

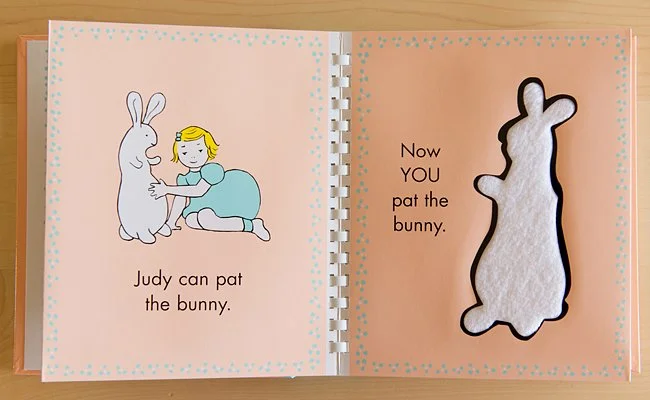

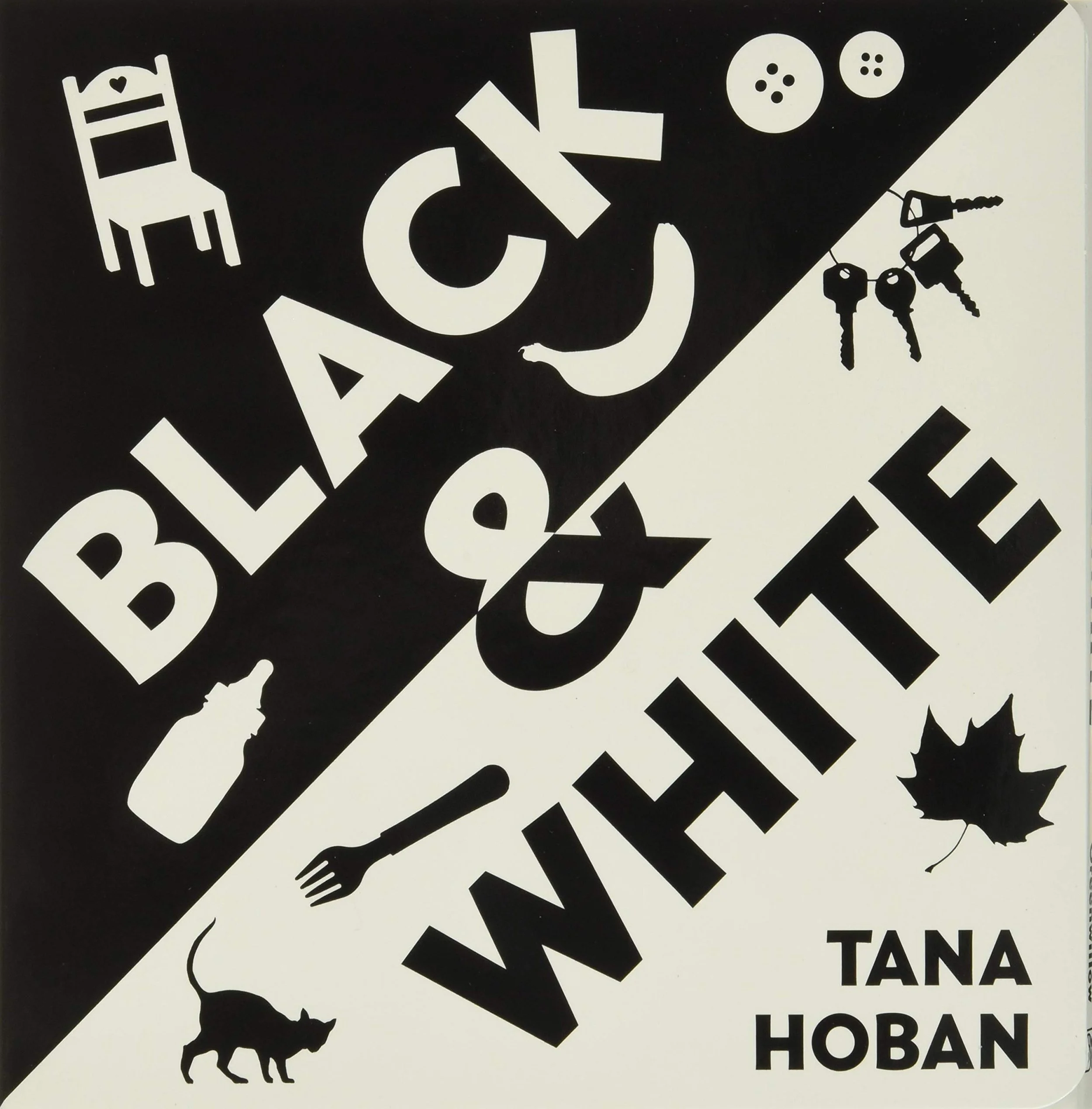

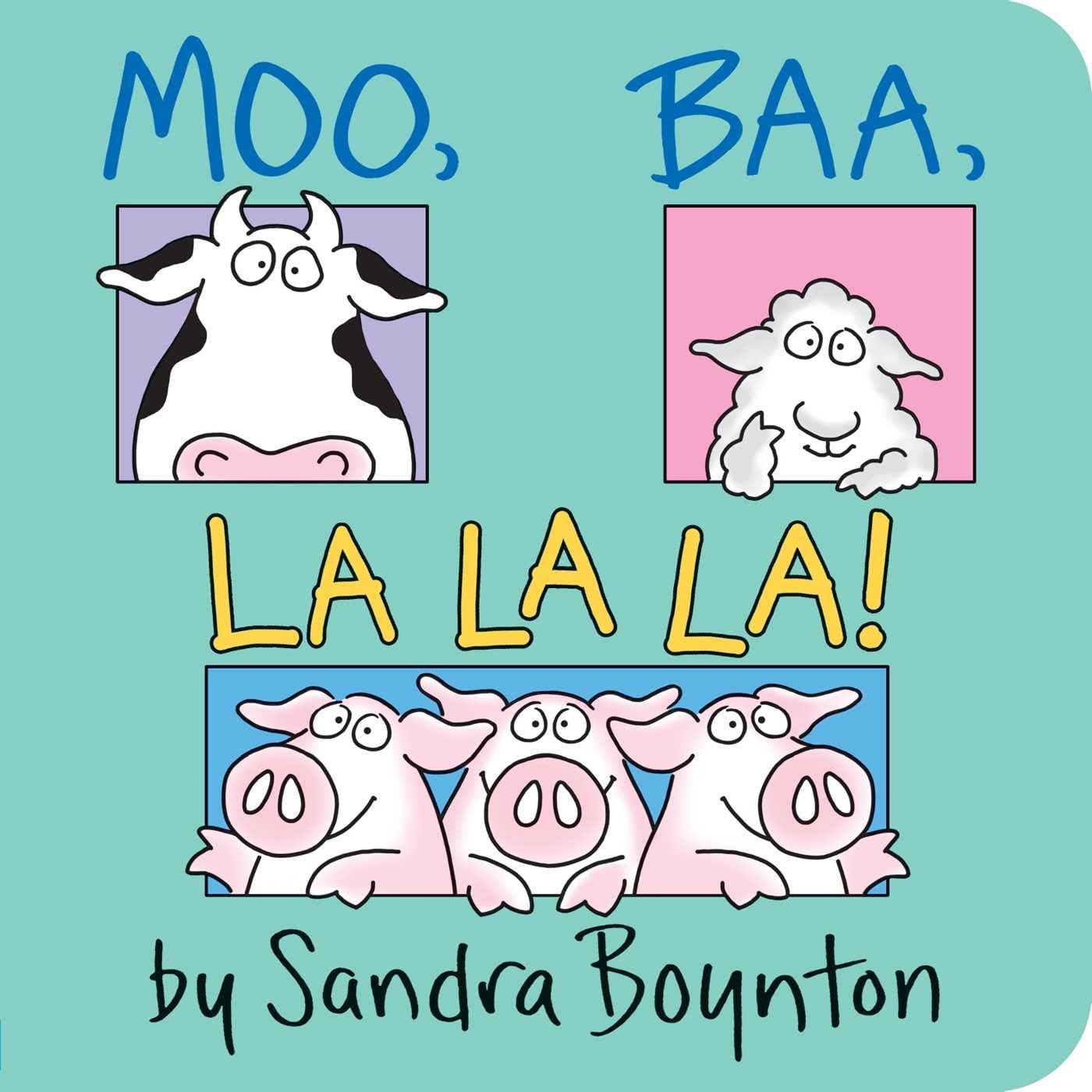

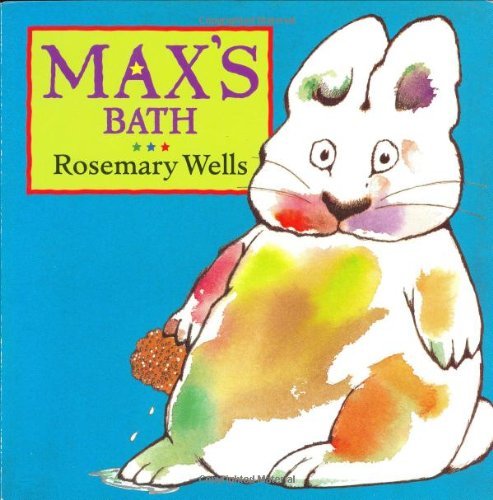

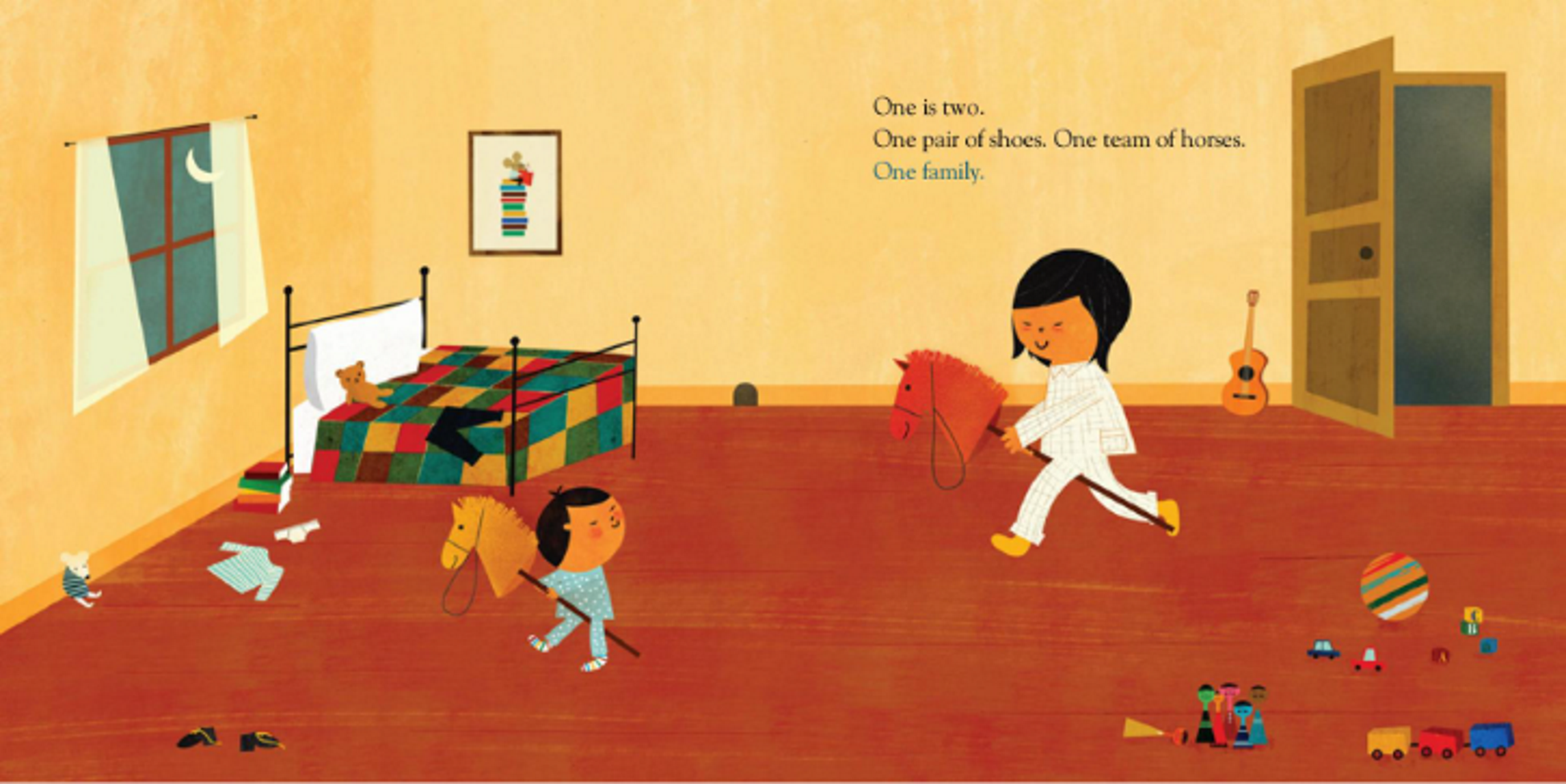

Picture Book:

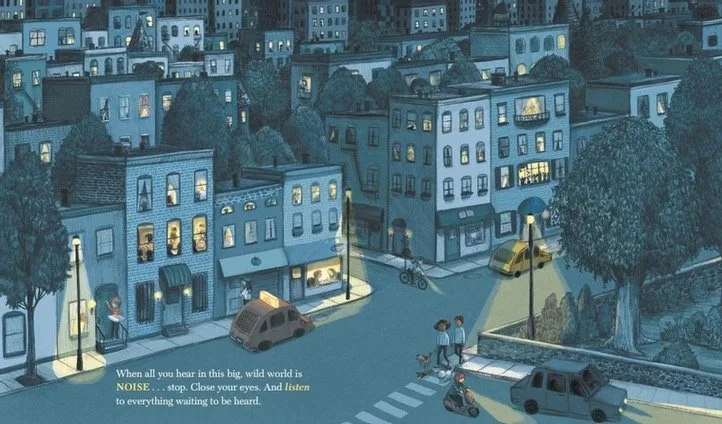

A magical container for words and pictures working together.

Me Just now.

Once upon a time… a few author-illustrators began to write books, not to tell stories, but to satisfy children’s curiosity about the world. For a while these fact-but-not-dusty-dry-fact books had the bookshelves in bookstores and public libraries all to themselves.

Richard Scarry’s Best Word Book Ever by Richard Scarry

Dinosaurs, Dinosaurs by Byron Barton 978-0690047684

Boats by Anne Rockwell 978-0140549881

Manners by Aliki 978-0688045791

Tornados! by Gail Gibbons 978-0823441877

Sometimes they sat on the shelves with the storybooks, sometimes they sat with the field guides and how-to books on the shelves for bigger kids. But the curious children who needed them always found them.

A brief detour into the world of publishing is needed to appreciate how unique the Expository Picture Book really is. Non-fiction books for children have mostly been produced for the school and public library market. “Just-the-facts” books on one subject or concept, usually about science, technology, engineering, geography, social studies, or math, with big chunks of text and sidebars, with a table of contents, index, and glossary. The books are meant for students to use for research, not read for enjoyment. (Though plenty of kids do.) The author’s voice is formal, as is the language.

The books are published in sets, at different reading levels, and per-book, are expensive enough to give school librarians and public library librarians angina.

Publishers like ABDO, Enslow, Capstone, Cavendish Square, Child’s World, Gareth-Stevens, and Lerner use in-house staff or authors-for-hire to write their series.

Celebrating Holidays: Celebrating Chinese New Year 978-1503853829

Earth’s Four Spheres: The Atmosphere 978-1502664341

Community Helpers: Pilots 978-1503858336

Two non-fiction publishers; Dorling Kindersley and Scholastic, have one foot in the school and public library market, and one foot in the retail market.

Children Just Like Me by Barnabas and Anabel Kindersley 9780789402011

The DK Eyewitness series, with colorful photographs and spare text, made an impact on traditional publishing when they debuted in 1988. The success of the Eyewitness series incentivized non-fiction publishers to put as much thought into exciting design as in the quality of information.

The DK Eyewitness series became a retail staple, and interest in non-fiction books for children began to boom. Children and parents wanted more, and the publishing world was happy to comply.

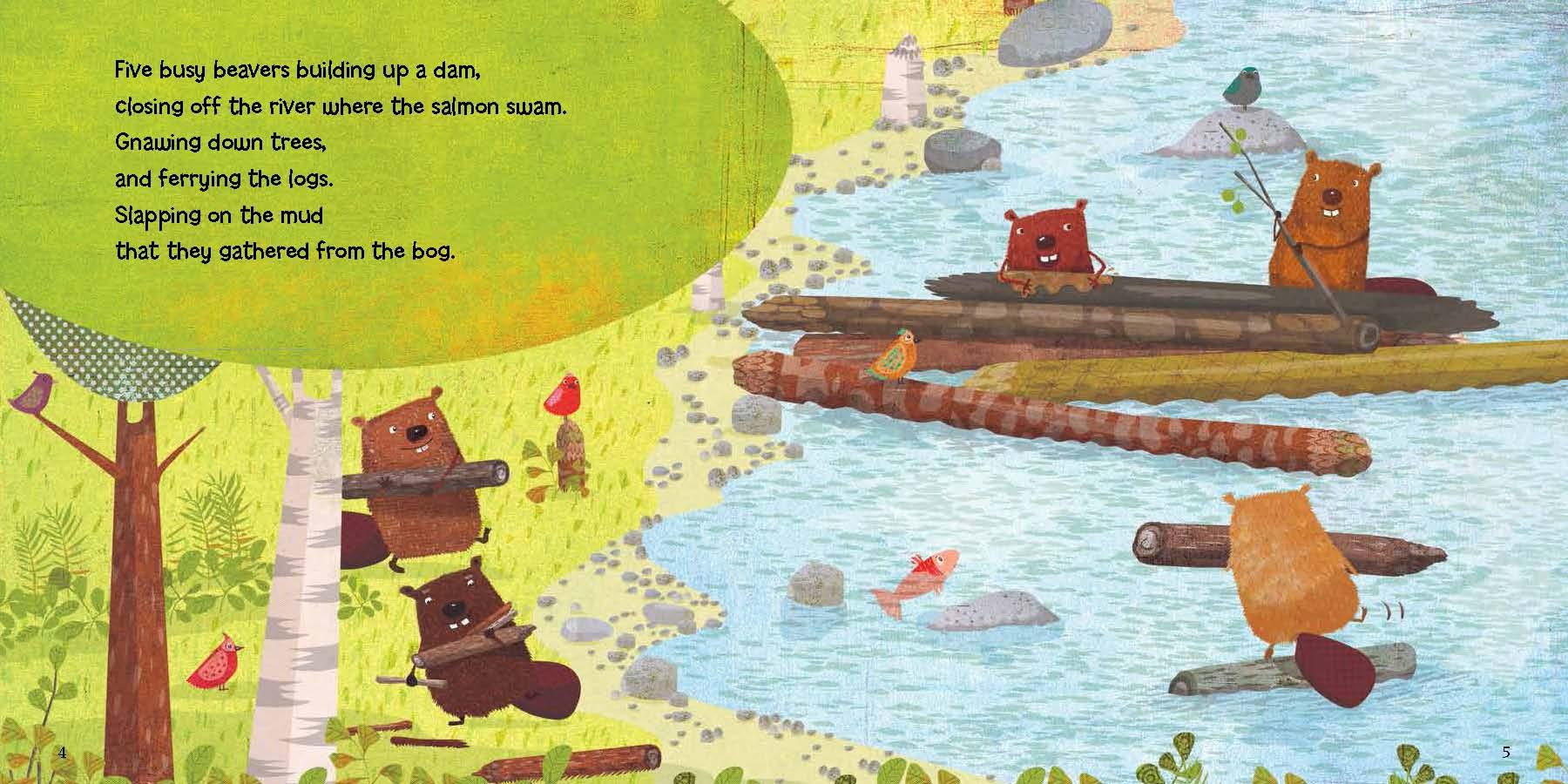

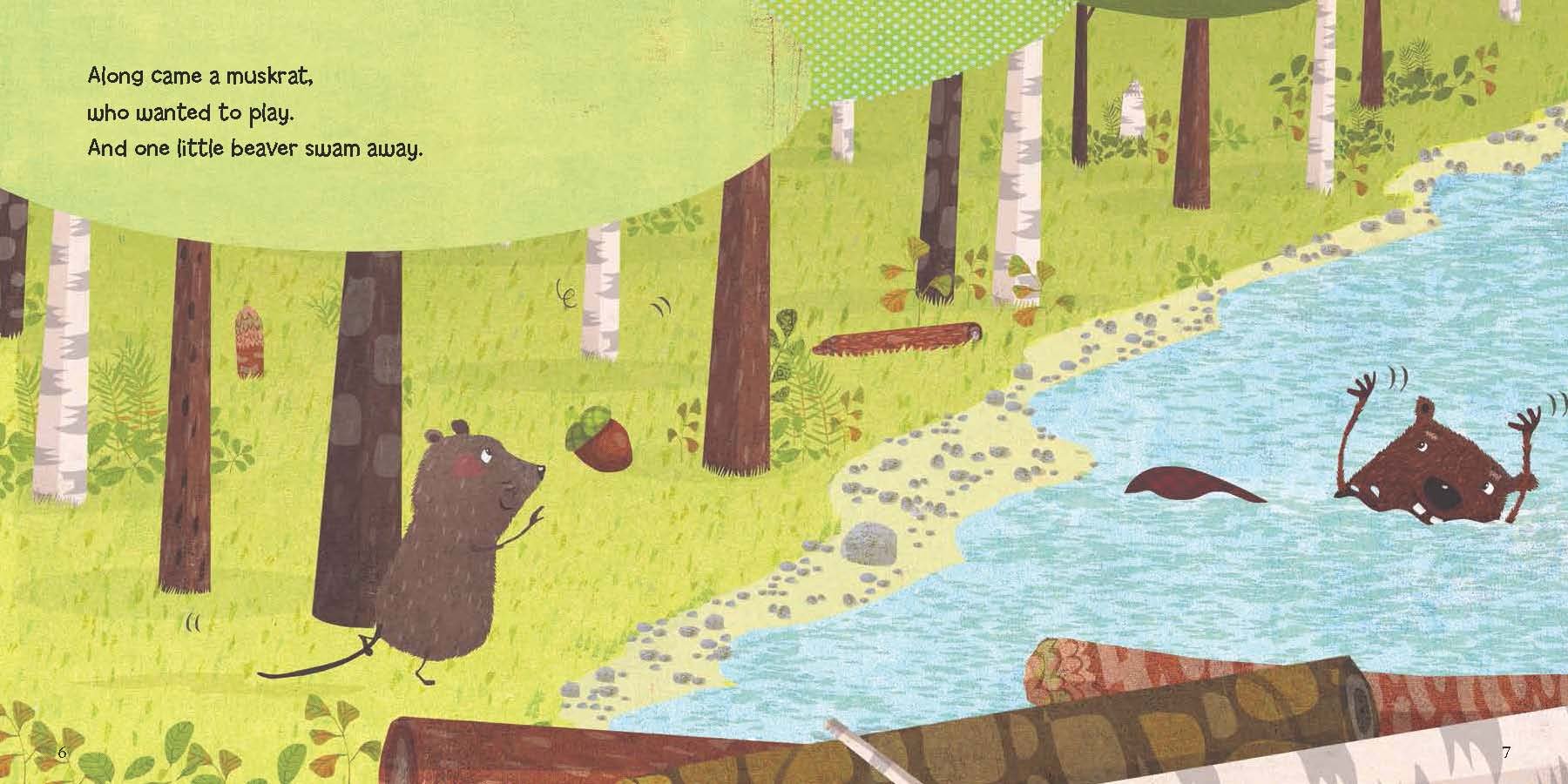

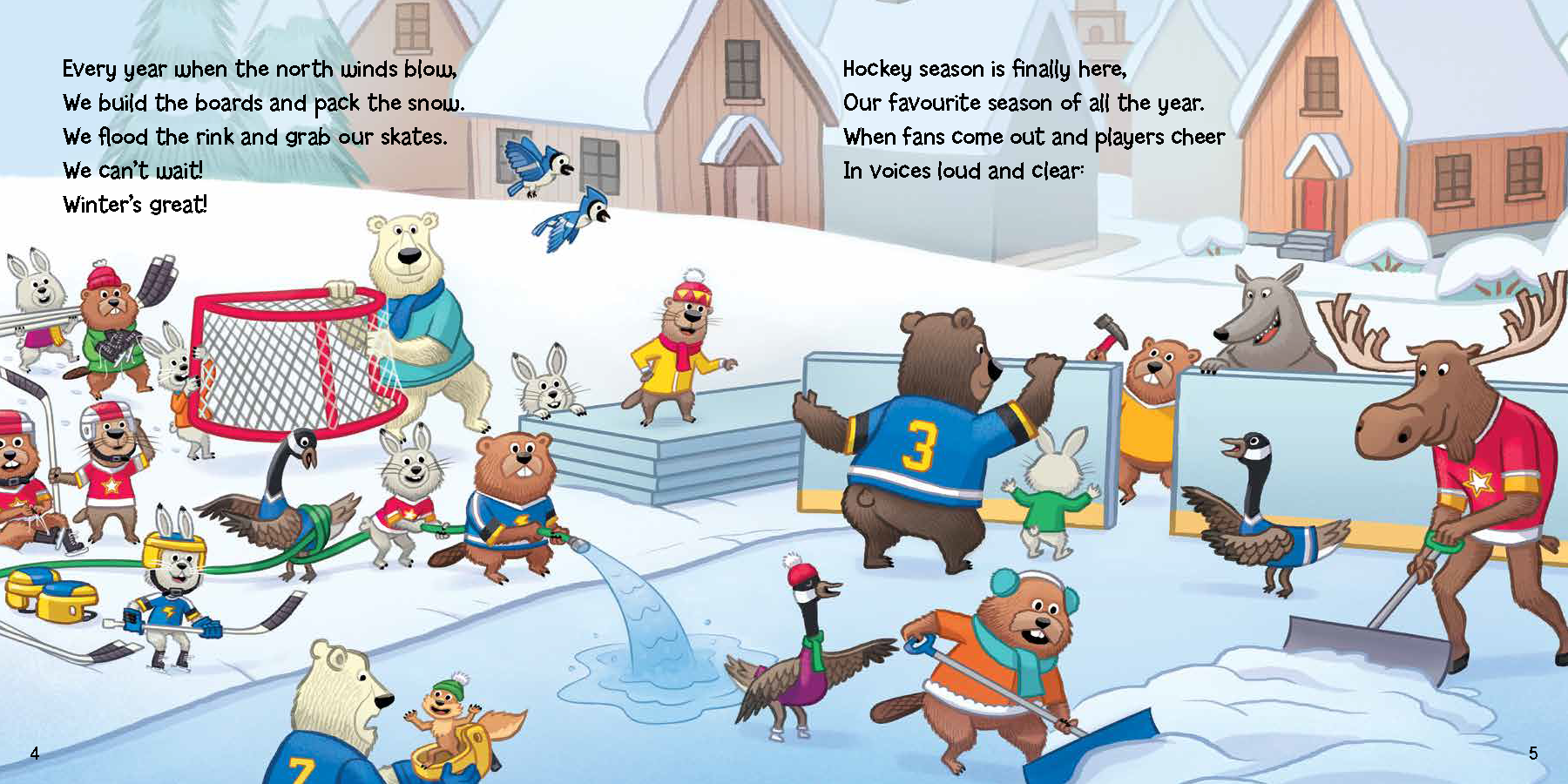

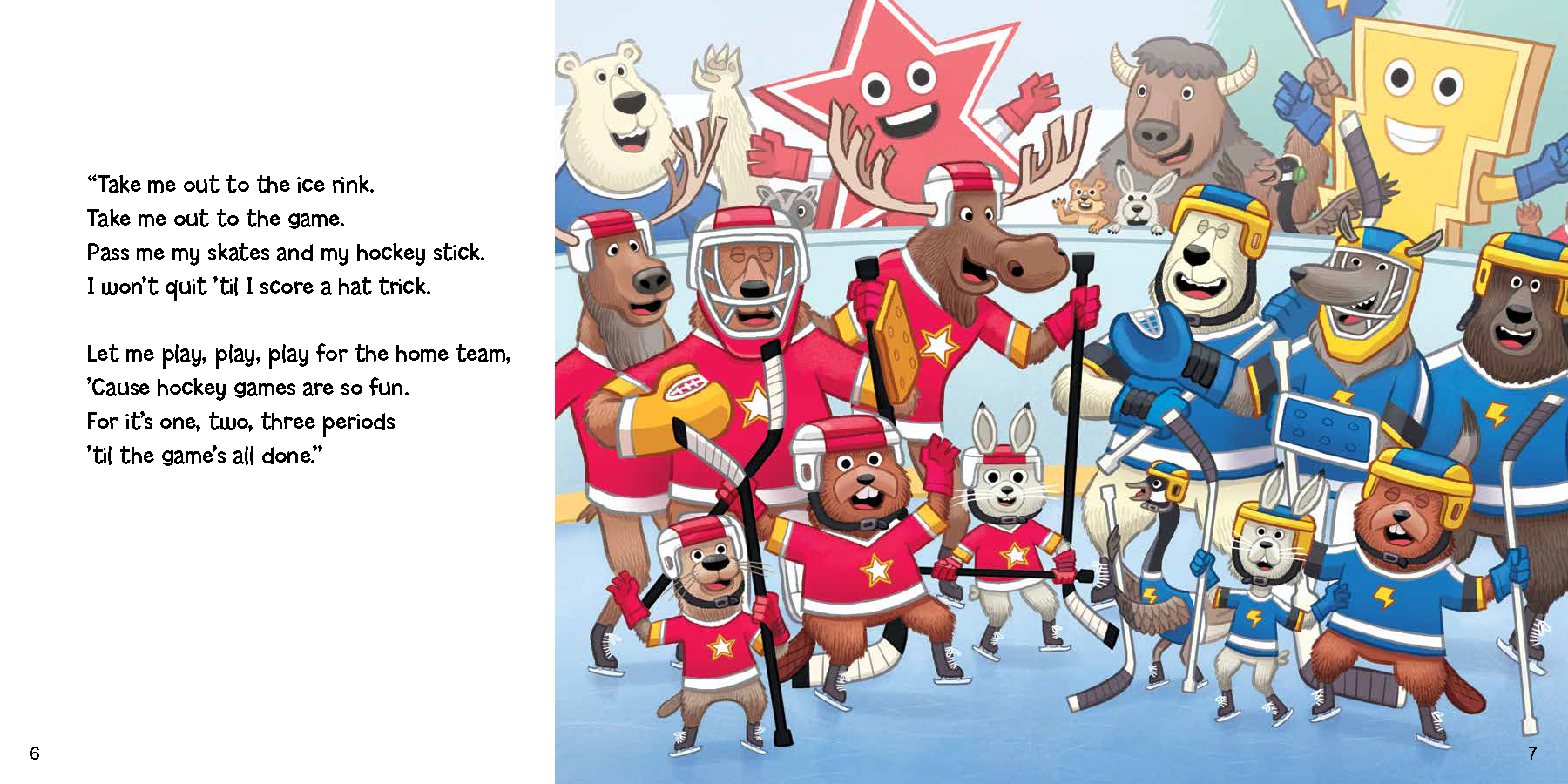

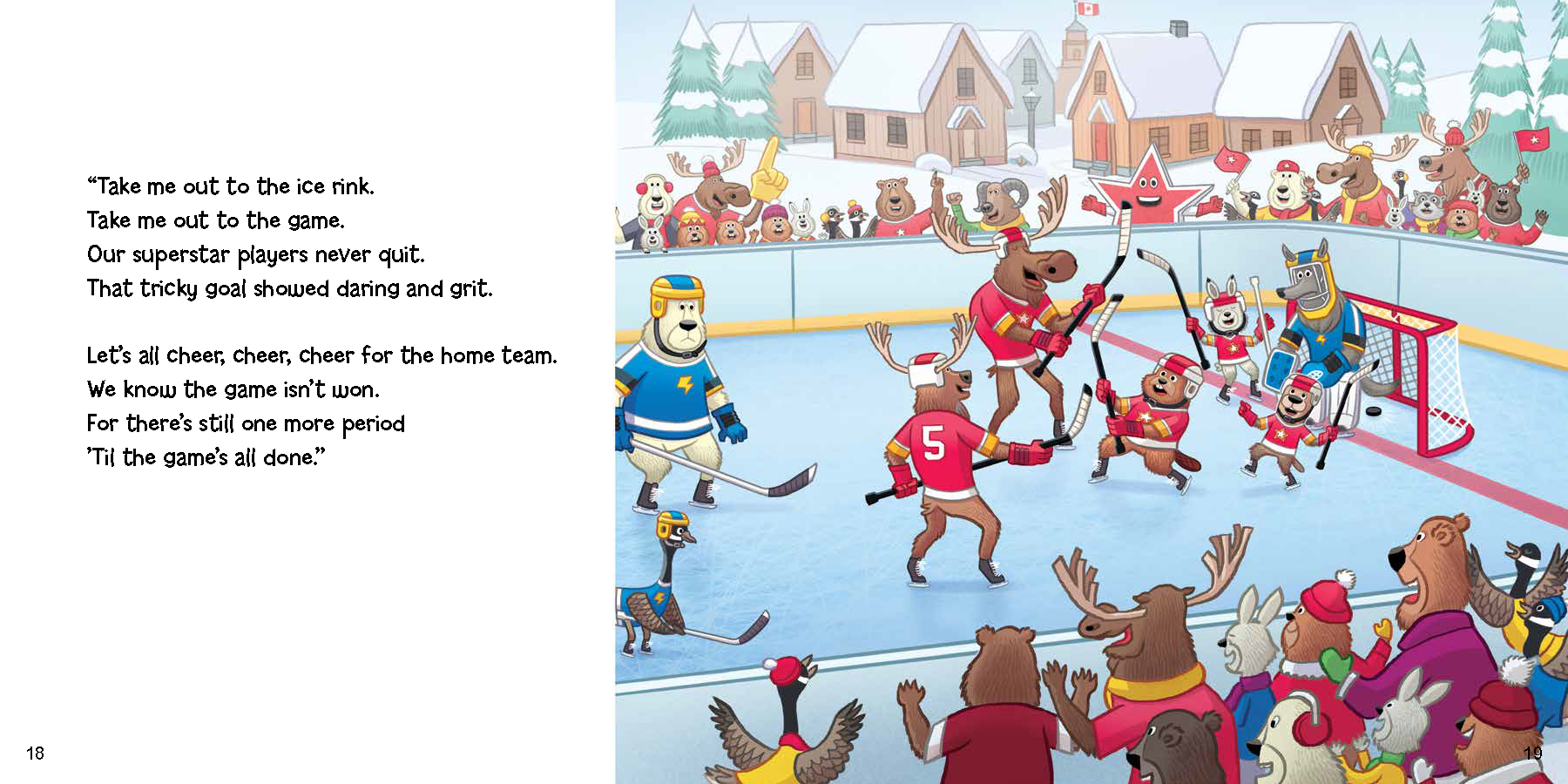

In contrast to the made-for-research books, Expository Picture Books are delightfully idiosyncratic. The author’s voice is playful, and facts are presented in informal ways, as if the author is in conversation with the reader. Humor is often served up in both the text and the illustrations, without losing the authenticity of the subject matter.

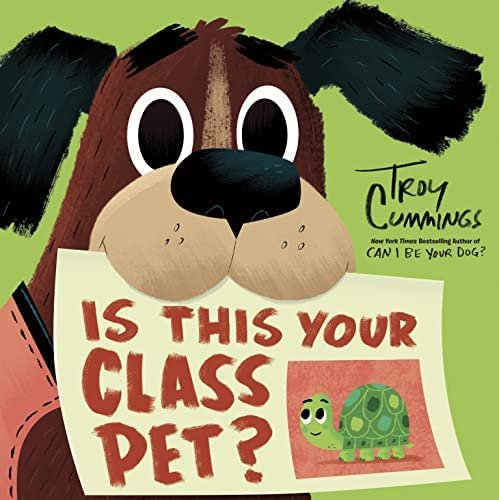

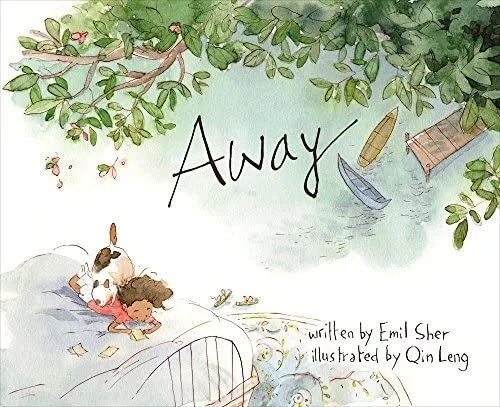

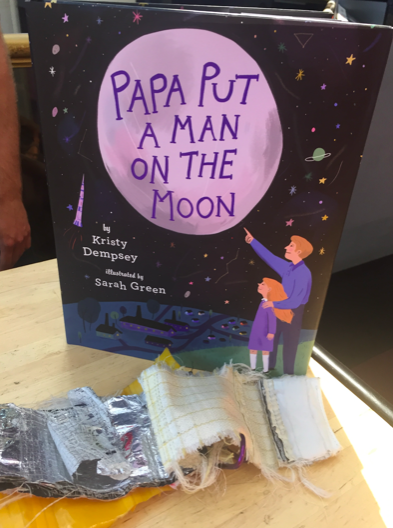

Here are some examples of recent books that entertain while educating.

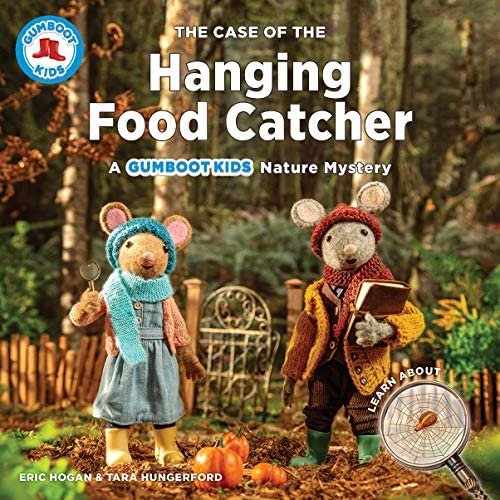

The Case of the Hanging Food Catcher by Eric Hogan and Tara Hungerford 978-0228103387 [This has as much story as it does information, but these nature mysteries are too darn cute not to include in this list.]

Tiny Dino by Deborah Freedman 978-0593352649

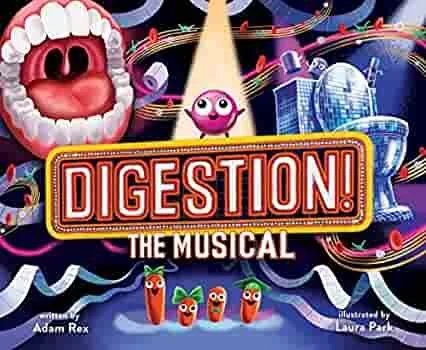

Digestion! The Musical by Adam Rex and Laura Park 978-1452183862

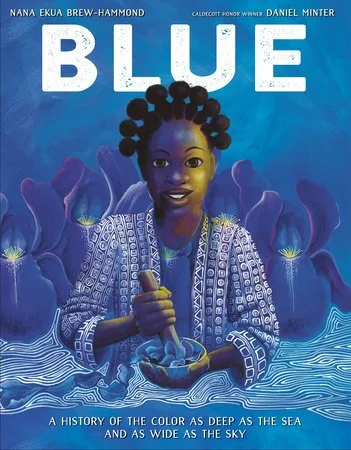

Blue by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond 978-1984894366

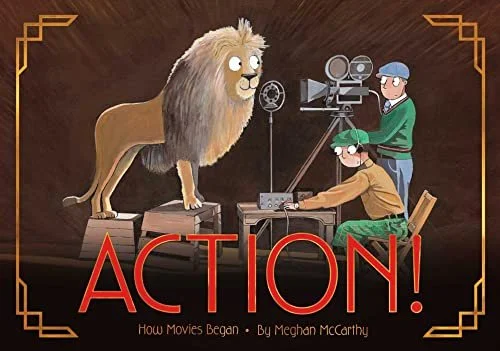

Action! How Movies Began by Meghan McCarthy 978-1534452305

Check out the Kirkus Review’s “Best Nonfiction Picture Books of 2022” at www.kirkusrevies.com/Book-lists/best/nonfiction-picture-books-of-2022 for more great expository picture book picks!