BLOG

Recent Blog Posts

Picture Book Writing Challenge

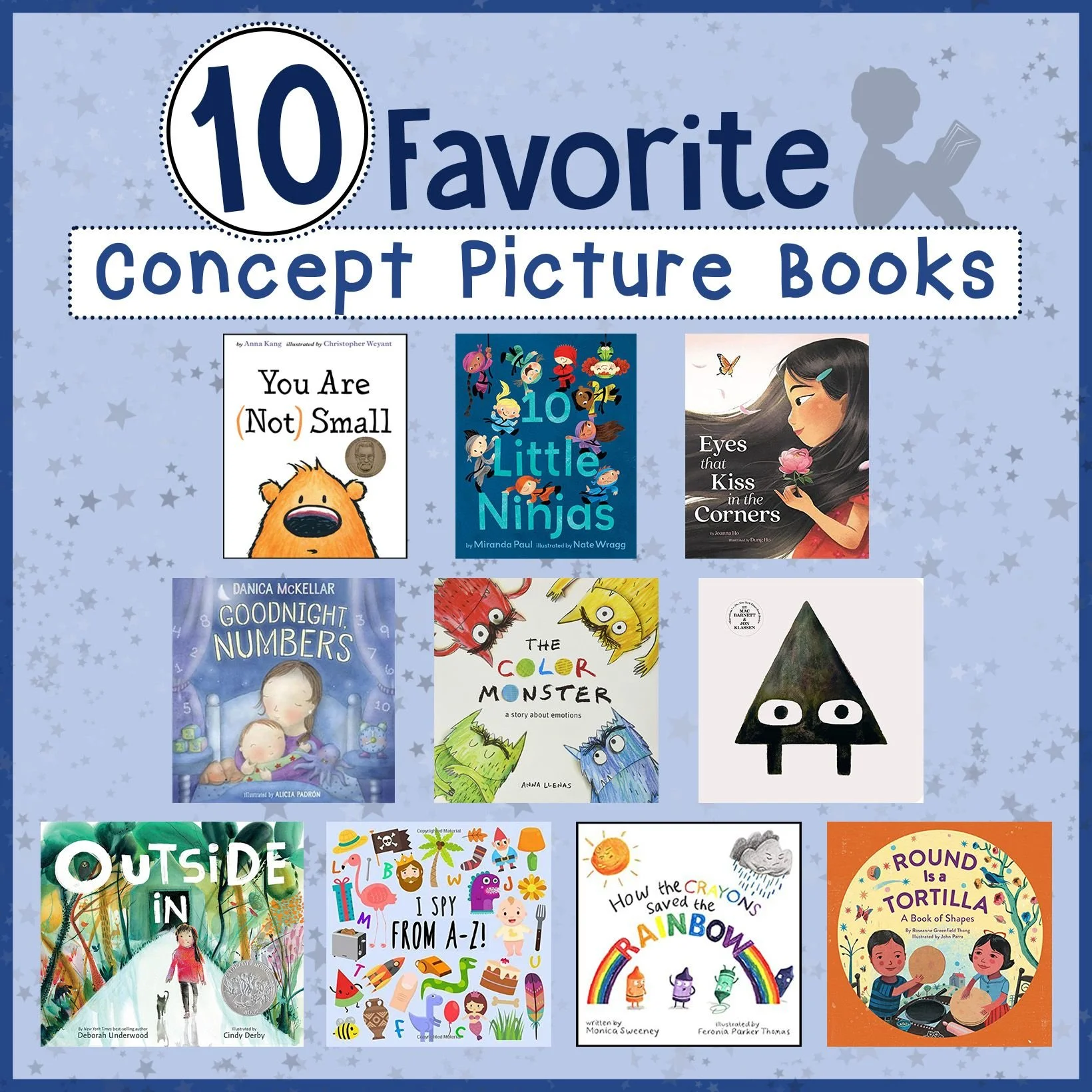

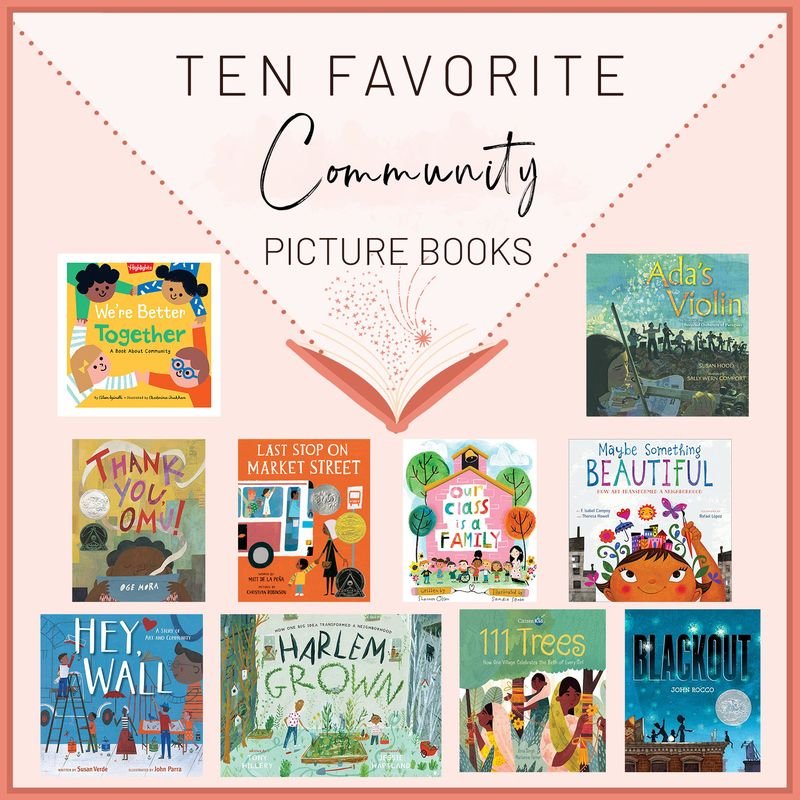

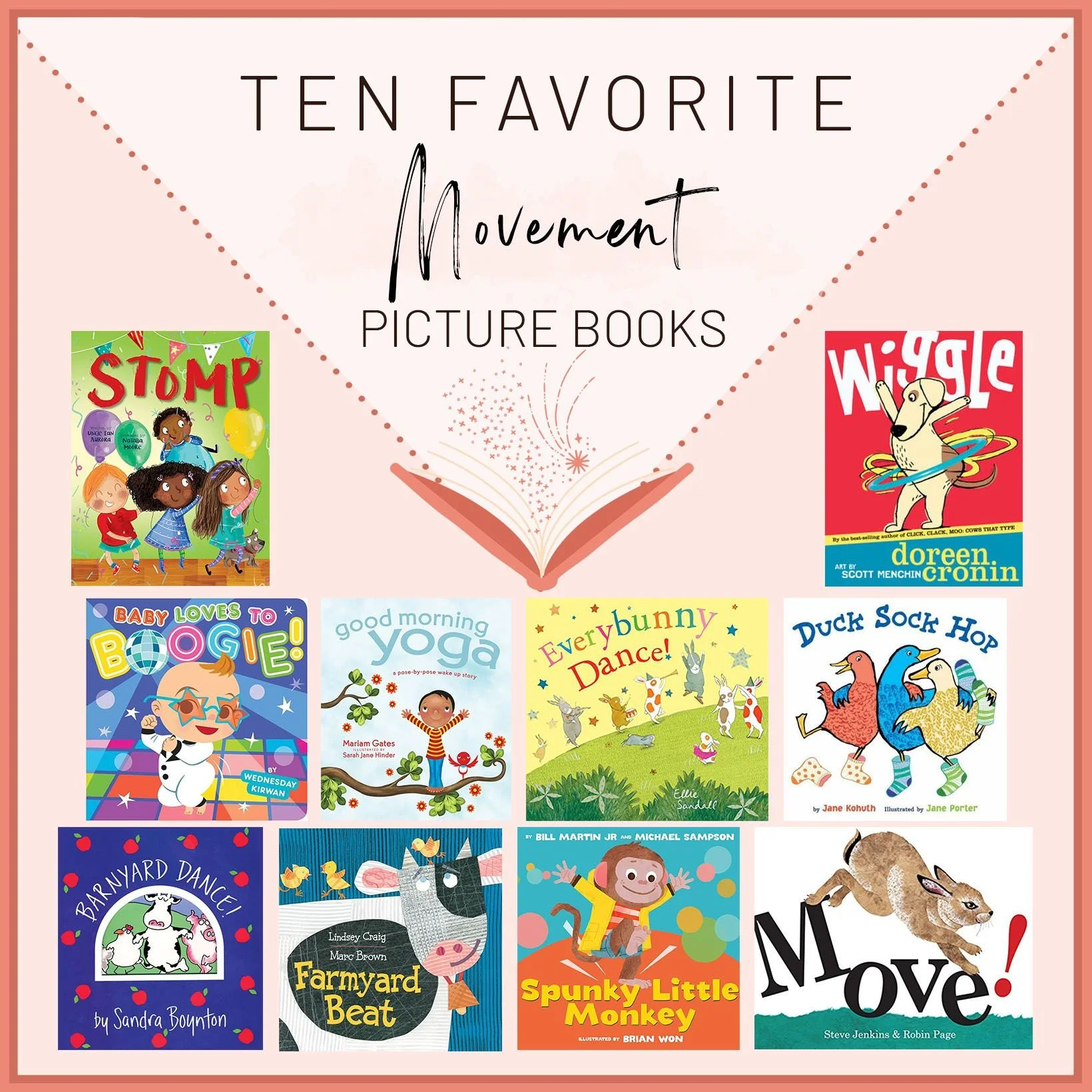

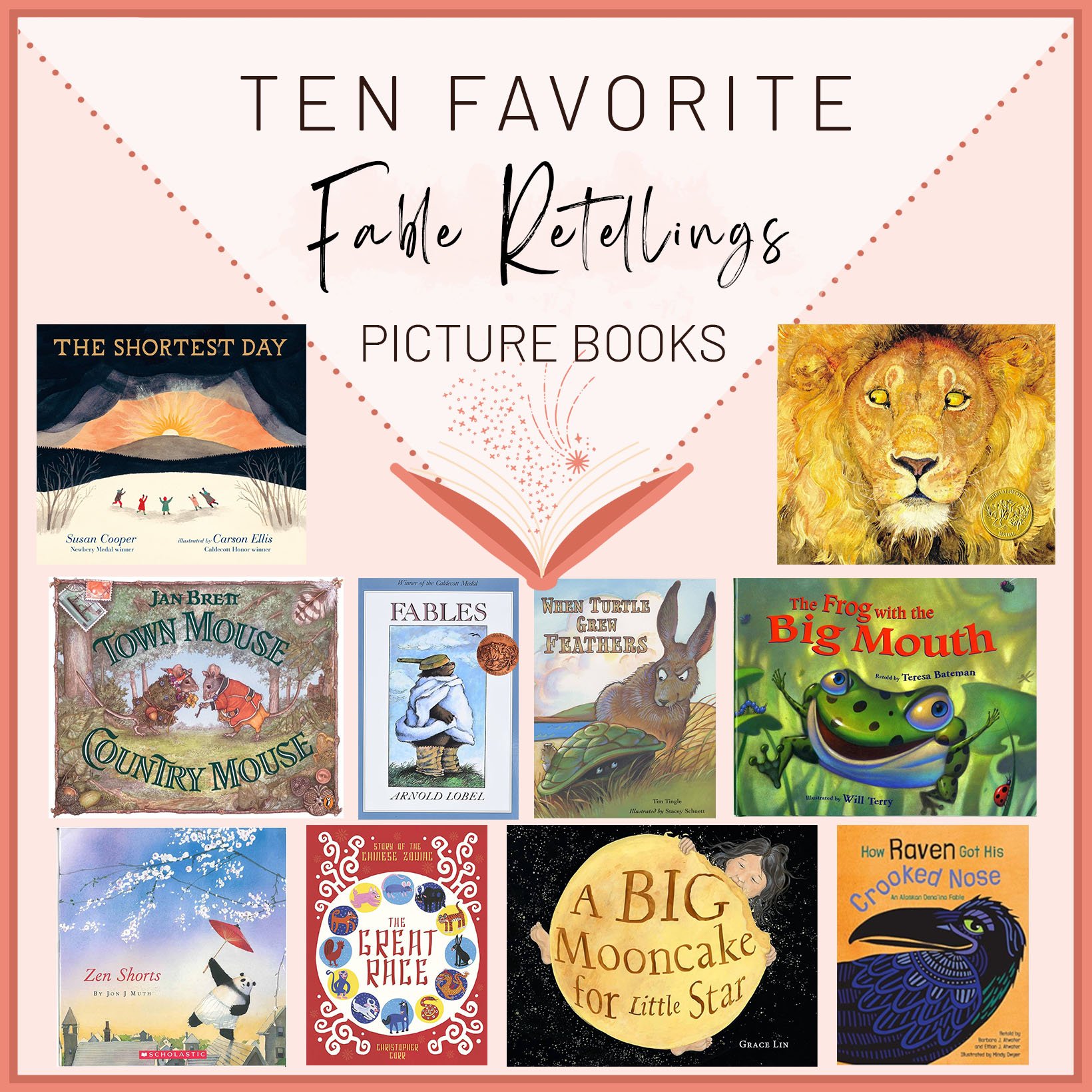

Favorite Book Lists

Storytime

Book Clubs

Author/Illustrator Interviews

For Writers

Archives

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- July 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015