We are so excited to have Liz Garton Scanlon join us today to share information about Journey Picture Books!

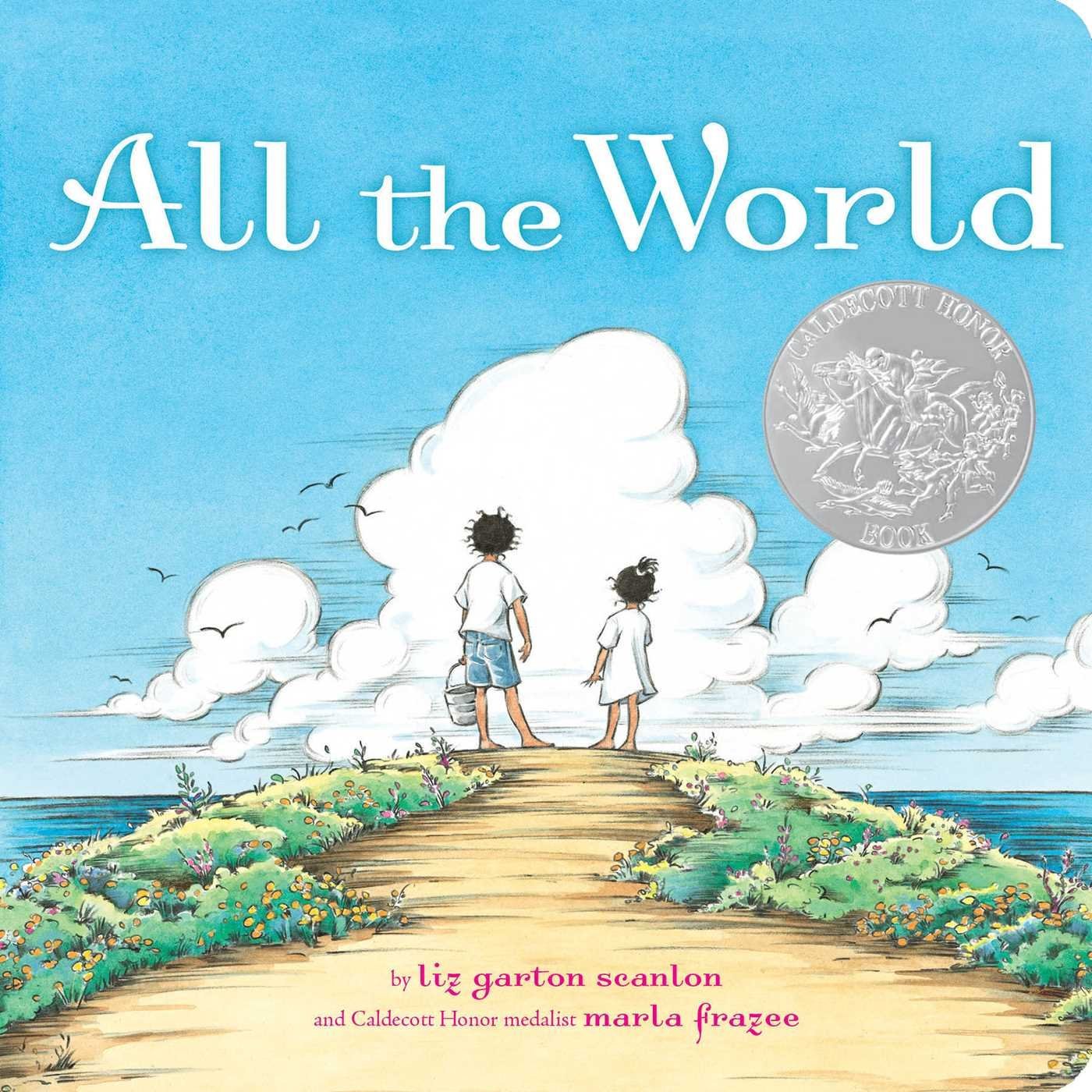

Liz Garton Scanlon is the author of many beloved books for kids, including the recent middle grade novel Lolo's Light, the upcoming picture book Full Moon Pups, the Caldecott honored All the World, and many others. Liz is faculty co-chair of the Writing for Children and Young Adults program at the Vermont Faculty of Fine Arts, and lives in Austin, Texas. Find more on her life and work at www.LizGartonScanlon.com

In a game of writerly free association, I’d say journey and you – most likely – would say hero’s. The Hero’s Journey is a story template (popularized by Joseph Campbell) that begins with the hero’s call to adventure, follows him on said adventure, and welcomes him back home, victorious. It’s a way to tell a journey story, for sure. But it’s not the only way.

For one thing, it presumes that only certain, extraordinary characters receive the call when really, life itself is the adventure and if we’ve been born, we’ve been called. It also suggests a journey that’s circular and complete – the hero goes out, faces challenges, learns stuff about himself and the world, and returns home smugly satisfied. For most of us, life’s journey is more like a spiral than a circle, with plenty of side trips and twisty tentacles along the way. And while we certainly learn and grow as we navigate circumstances and interactions, we rarely (if ever) feel complete, much less smug! Finally, the Hero’s Journey is gendered in a way that’s untenable for many writers, readers and adventurers these days.

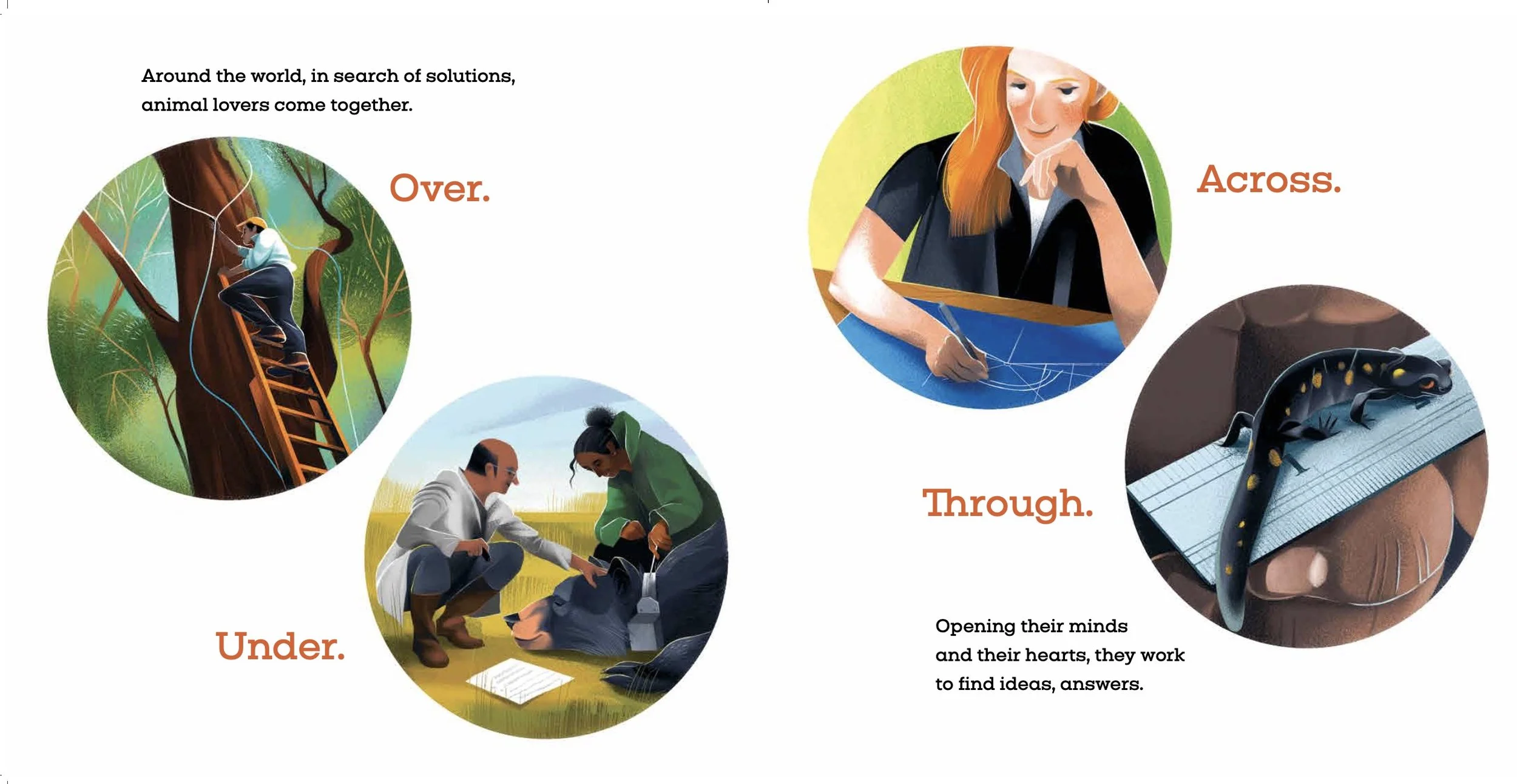

So, where does that leave those of us who want to use a journey as story structure or subject matter? Well, if we explode open the limitations around the Hero’s Journey, we see that we’re all on chosen or assigned adventures all the time, and every single one is an act of imagination. We do not know what we will encounter along the way, and yet we move forward – bravely or naively or with deep trepidation or fear – through space and time – fired by need or desire or curiosity or wonder. Sometimes, at the end, we return home, but not always. Sometimes, we’re dramatically changed, but not always. Sometimes, we feel satisfied, but not forever.

I’ve written several journey-based books over the years. I’m thinking of my picture book In the Canyon, illustrated by Ashley Wolff, that tells the story of a girl who hikes to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and, in the end, rather than feeling victorious, feels deeply connected to the natural world. My first middle grade novel, The Great Good Summer, is built partly around a road trip that Ivy and her best friend Paul take via Greyhound Bus, which we can all agree is more humbling than heroic.

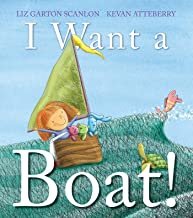

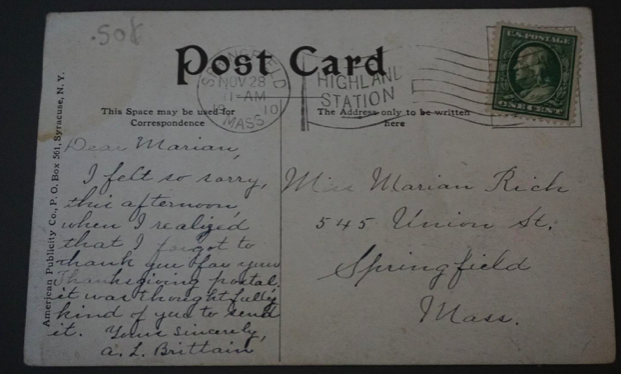

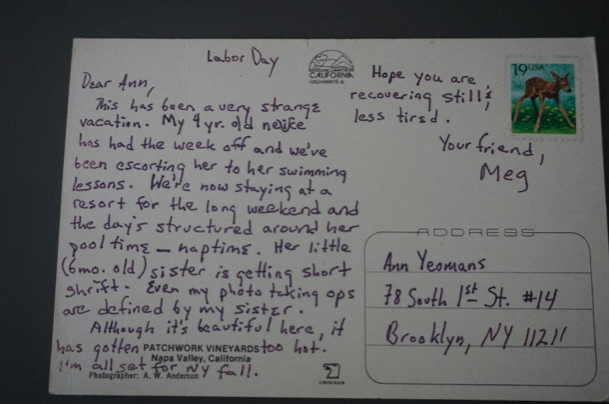

But today I want to take a look at I Want a Boat, my collaboration with illustrator Kevan Atteberry. In this book, the protagonist is a young girl who uses her imagination to turn an empty box into a boat and, with that, she’s off an a seafaring adventure, with only her stuffies to serve as crew. The lyrical structure of this book is the repeating phrases I have… and I want…, phrases that were originally introduced to me as journaling prompts by a therapist-friend. The idea behind the words, at least as I understand them, is to express gratitude and presence (I have…) and also, a yearning, a desire, a leaning toward what’s next (I want…)

This, to me, is what moves a story forward. A grounding in the present moment and a pushing off from there. An understanding of where the character is, where she is headed, and what is moves her in that direction. There is no true template to guide that movement or predict the actual, eventual destination, whether we wish there were or not. The character, like the writer, can only be curious about the journey. In turn, the reader will be, too.

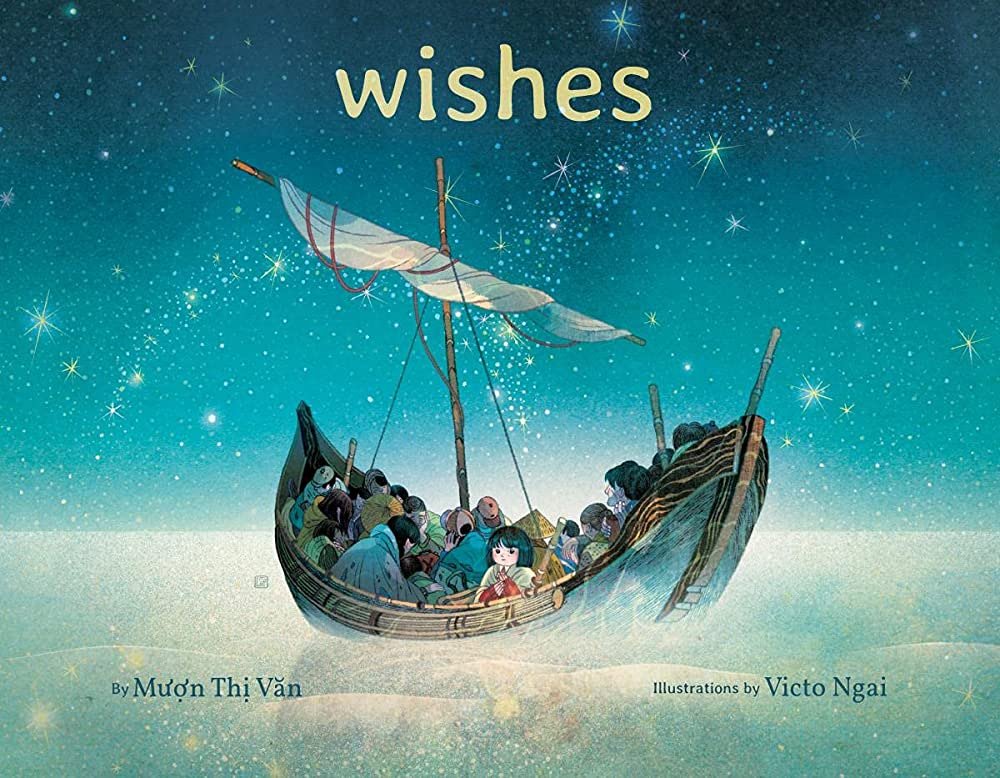

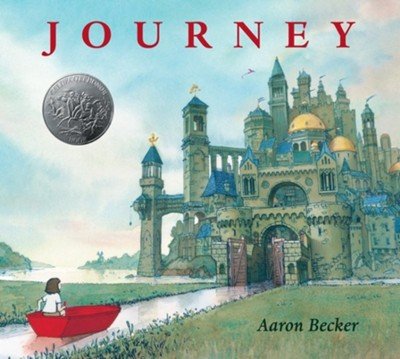

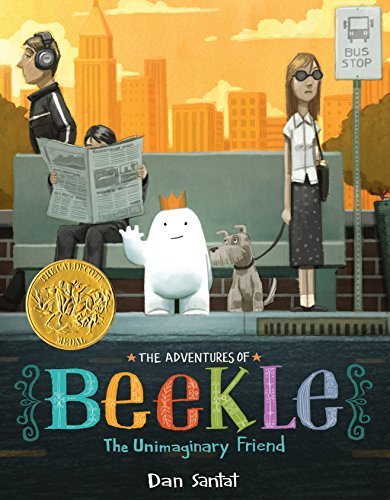

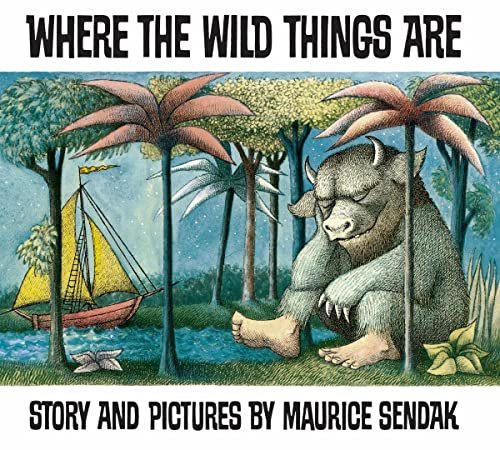

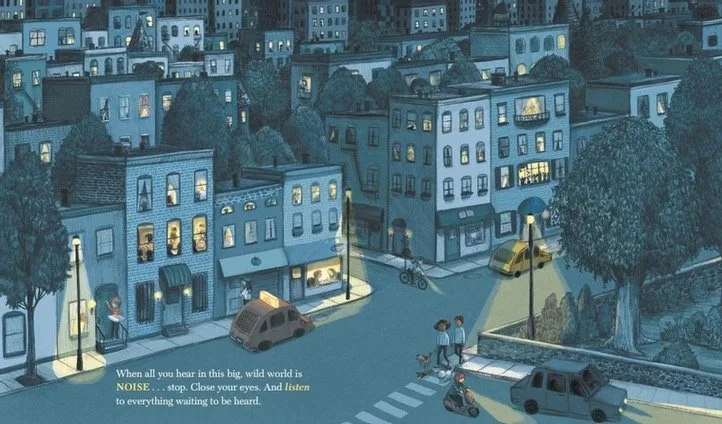

(For more journeys, have a look at Liz’s Would You Come Too? and Frances in the Country, as well as Wishes by Victo Ngai and Muon Thi Van, Journey by Aaron Becker, The Adventures of Beekle by Dan Santat, and the very classic Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak.)

Thanks so much for joining us, Liz!